Like most people living in the affluent West, I grew up with a pretty limited exposure to “dal,” which is the catchall term in India for dozens of varieties of dried lentils, beans, and peas.

Dal also refers to all manner of Indian soups and stews that non-Indians call curries. Dal is made from dal. Hope that makes sense?

You may also have heard of the Western term for dal, which is the pulse.

Pulses and dal are exactly the same thing. They are dried seeds of leguminous plants.

What’s different is that the variety of dal used in Indian cuisine is beyond what most Westerners have seen, or are familiar with.

I created this ultimate guide to Indian dal to help you understand:

- Why Indian dal is getting more popular

- The benefits of consuming dal

- The differences among dal, broken down between those that are widely available at North American grocery stores, versus those that must be purchased online or at Indian stores

- How dal is used in recipes

- Where you can buy dal

How I Expanded From Beans To An Appreciation Of Dal

Since I am a non-Indian, and you likely are as well, I’d like to start with a brief cultural history of the pulses we are already familiar with, since they also play a minor role in Indian cuisine.

This section will also be helpful for my Indian readers, who may not have a good understanding of how pulses are used in North America.

This cultural assessment is based on my own experience growing up in Western Canada, and my later observations as a New Yorker.

To start us off, I'll say that one of the most popular pulse dishes in North America is known as chili.

Chili is a comforting Tex-Mex dish typically made from ground beef stewed with tomatoes, Mexican chili powder, and beans. There could be any combination of black beans, pinto beans, and/or kidney beans.

Another popular dish we have here is the marinaded bean salad, which involves a multicolored collection of giant cooked beans mixed with long green beans, red peppers, and onions, coated in a sweet, vinegary sauce.

A bean salad like this would likely make its appearance at a buffet, deli, or church luncheon as an accompaniment to sandwiches.

Then there are the soup beans.

In my childhood home, once in a blue moon a few beans would appear in a store-bought soup, such as a minestrone or the occasional split pea soup.

Split pea soup was always an oddity for me, based on its muddy texture that reminded me of baby mush.

Lentils of the green-brown variety made even fewer appearances than the beans. Again, mostly as a minor ingredient in soups.

To sum it up, my experience as a typical North American (who is now middle aged) is that pulses were relegated to occasional dishes that weren’t particularly appealing.

Pulses were simply not treated as a meaningful option for a main course dish.

You may have a similar understanding of pulses, but you’re here because you are ready for a shift in perspective.

You want to be a dal convert, and enjoy the benefits of an affordable, flavorful, nutritious, food source.

If this is the case, then you are in the right place!

Indian Dal Is A Quick, Nutritious, Affordable Dinner Solution

Before gaining an appreciation for Indian dal, and using my heart to cook the dal and experience it, I realized I was seriously missing out!

After marrying into an Indian family, I discovered how easy it is to make a satisfying dinner with dal.

These days, I cook a batch of dal once or twice a week, in addition to my Western foods. (However, this is still nothing, because in India, dal is eaten daily.)

Dal is the primary protein source for vegetarians in India. Just a half cup of cooked dal contains 8 grams of protein of 7 grams of fiber.

I think all of you can appreciate the affordability of dal versus meat. According to Consumer Reports, a serving of pulses costs about 10 cents compared to $1.50 for a serving of beef. There is no contest.

In my experience, it feels really good to have jars of dal in your cupboard, because you know that you can easily take out a cup or two and soak it in cold water in anticipation of a tasty dinner later. If you have a pressure cooker, or an Instant Pot, it is even easier to cook dal.

In fact, I was so taken by dal that I created a Buttered Veg Indian dinner concept that helps Westerners make sense of Indian cuisine.

The simple Indian dinner includes basmati rice, any dal, a gently spiced vegetable (or not), and a condiment.

This is my go to vegetarian dinner plan for when I want a healthy, comforting meal filled with nourishment and satisfaction for mind and body.

A big batch of Indian dal can be made once, and turned into multiple meals. You can have dal as a second meal the next day, or freeze it for a future dinner.

To reheat, just add a touch of salt, and your dal is just as good as the first day you made it. Guaranteed! And you cannot say this about most leftovers.

Why Pulses Are Growing In Popularity

Despite their widespread consumption around the world, the popularity of pulses is growing only in tiny pockets.

The first pocket comes from people like you who understand the health and environmental benefits of pulses, and are looking for more information.

Traditionally, a dearth of relatable recipes, lack knowledge about how to cook pulses, dissatisfaction with long cooking times, and a reluctance to use canned pulses, has limited their popularity.

Food trends that emphasize ethnic foods and flavors, as well as the Instant Pot, which makes cooking pulses as simple as pushing a button, are opening new doors to our understanding of cooking with pulses.

Two other big growth areas we’ve seen in North America are the hummus revolution and the yellow pea revolution.

As evidence of our love affair with hummus, in 1994 the United States harvested about 30,000 acres of chickpeas annually, and in 2018 that number had grown to a whopping 859,000 acres.

On the other hand, yellow pea production grew after food scientists discovered how to make yellow pea protein taste good, and food manufacturers caught on to the health benefits of this new ingredient.

No longer are we reliant on soy for plant-based protein. The yellow pea is actually one of the primary protein sources in the popular plant-based burger known as The Beyond Burger.

Why Do Keto And Paleo Diets Exclude Pulses?

Oddly, pulses are excluded within the paleo and keto community for not being part of our ancestral diet (this claim has been challenged by some researchers), and for their so-called anti-nutrients.

Two of the main reasons some advocates say people should avoid pulses is due to their phytic acid and lectin proteins.

Phytic acid is said to bind to nutrients, and prevent your body from absorbing them, and lectin is difficult to digest for a variety of reasons.

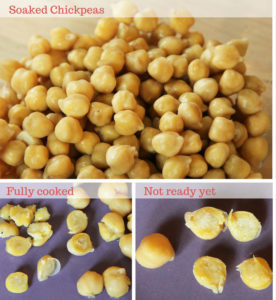

However, soaking and cooking pulses before eating them completely inactivates the lectins and greatly reduces the phytic acid content in the pulses.

Further, pulses are not the only foods that contain phytic acid. Nuts are also full of it.

In reading many opinions about pulses on the Internet, it seems to frequently boil down to pulses not being as good as meat.

Okay. Point taken. They aren’t as good.

But what if you don’t want to eat meat, or you want to reduce meat? Or you can’t afford meat? Or you really enjoy eating pulses because they taste amazing, or pulses are part of your culture?

Or maybe you really believe in the environmental benefits of enjoying pulses.

Pulses are incredibly beneficial to farmers due to their nitrogen fixing properties. A larger market for pulses would literally transform our agricultural system.

My conclusion, and that of some experts too, is that eating pulses as part of a nutrient-dense and healthy diet is a perfectly reasonable approach for most people.

The U.S. Dietary Guidelines recommends eating "a variety of protein foods, including seafood, lean meats and poultry, eggs, legumes (beans and peas), and nuts, seeds, and soy products."

Intro To The Indian Dal Pantry

You may have already guessed that my childhood ended well before the hummus revolution - haha.

It was also before North Americans opened up to the idea of exploring ethnic cuisines beyond Italian, Americanized Chinese, and a bit of Mexican. (And thanks Mexico for introducing us to rice and beans, refried beans, and bean burritos!)

There is no doubt that our food preferences are changing.

North Americans today—especially young people—are way more open to exploring new foods and flavors.

However, it was still one fine day that I got a HUGE crash course in dal.

You can get a particular dal with the skin, without the skin, split with the skin, and split without the skin. That’s four versions of the same dal.

My mind was blown when my future husband took me to an Indian vegetarian restaurant for the first time and I saw dozens of menu items made with dal!

How could they all be different, I asked incredulously?

Shocking.

Yes.

But true.

When I say there is a world of pulses out there beyond black beans, pinto beans, kidney beans, and brown-green or even red lentils (I have just listed what is commonly sold in American grocery stores.), I am not joking.

The Indian dal pantry represents a lot more of what the world eats, and the possibilities are endless.

In contrast to the kidney, fava, or edamame beans we are familiar with in the West, India’s most widely used dal are all tiny, which means it is way more digestible than larger beans.

The Indian dal pantry is also more diverse. There are dozens of pulse varieties, including different forms of the same pulse.

For example, you can get a particular dal with the skin, without the skin, split with the skin, and split without the skin. That’s four versions of the same dal.

This brings me to the next point. Indian cuisine is filled with dal, which is used to make every conceivable type of food, from soups and stews, to seasonings, to batters, to flours, to sweets.

As you learn more about Indian cuisine, prepare to be surprised by dal!

Is Dal Healthy?

Dal is among the world’s healthiest foods.

It is a fantastic source of vegetable-based protein, complex carbohydrates, B-complex vitamins, iron, folate, potassium, magnesium, zinc, micronutrients, and fibre.

Obtaining more fiber from dal could be incredibly helpful for most Americans, because most of us don’t get enough fiber, and experts tell us this is a problem.

Pulses are at the absolute top of the USDA’s list of fiber sources. The only other comparable source is high fiber bran cereal, which is a processed food.

Just half a cup of cooked dal contains up to 9.6 grams of fiber, according to the USDA, which is about ⅓ of the recommended daily allowance (RDA) for men and women between the ages of 31–50, and just less than a third of RDA for men and women between the ages of 19–30.

Dal is also very low in calories.

It provides a steady, slow-burning energy, and imparts a feeling of satiety due to its high protein content.

I encourage you to add pulses to your diet, so that you can obtain all these benefits.

RECOMMENDED RECIPE: How to Cook Chickpeas from Scratch —READ MORE

I intend to fill the Buttered Veg website with more and more recipes that will make you salivate for dal.

I predict that one day you will wonder how you ever lived without the complex flavor of something like Savory Chickpeas in Tangy Tomato Glaze, or Comforting Yellow Dal, served with steaming hot basmati rice and naan bread.

Is Dal Good For The Environment?

For all you out there who are looking to live lighter on the planet, pulses are a great way to satisfy your protein requirement with food that’s lower on the food chain.

In fact, the United Nations declared 2016 the Year of the Pulses to highlight them as an important source of food security.

Pulses are an important part of a sustainable food system in a number of ways.

As they grow, the plants (known as legumes) fix nitrogen from the air into the soil, which increases soil fertility and reduces the need for artificial fertilizers.

Legume crops are also drought resistant, and can grow without irrigation.

You don’t need to worry about genetically modified dal either, since it doesn't exist.

These highly nutritious crops could be truly life-saving one day if water and land scarcity increases as predicted.

You May Also Enjoy:

“Farmer Reveals the Surprising Potential of Pulses: Healthy, Low-Cost Protein for All” – READ MORE

“Mushy Peas? Not Anymore. Peas Are a Superfood!” – READ MORE

A Complete Glossary of Indian Dal

Intro To The Indian Dal Glossary

I hope I have given you enough information about dal to make you interested in trying some of the different varieties, and incorporating these nutritious foods into your diet.

To make it easy for you to give Indian dal a try, I have included recipes for each dal listed in the glossary whenever possible.

The glossary below will serve as a useful reference as you source dal for recipes on the Buttered Veg website and beyond.

The glossary is divided into three sections.

Items in the first section of the Indian dal glossary are usually not available at an average grocery store.

You will need to order these online, or visit an Indian grocery store.

Items in the second section of the Indian dal glossary are widely available at grocery stores in North America.

You will have no problem finding pulses such as kidney beans, chickpeas, yellow peas, and mung beans in any grocery store.

Items in the third section are specialty lentils, and you usually must source these from specialty stores, or online.

I have included these speciality lentils, because some of these do lend themselves to substitution for Indian dal, or they work well with Indian flavors.

I have left out the common pinto beans and black beans, since they do not have a tradition of use in India.

1: INDIAN DAL

Toor dal (without skin)

Also known as toovar dal or split pigeon peas

Toor dal is first in my personal pulse pantry, because it is the first new pulse I was introduced to in India, and it is a favorite.

Toor dal is popular in South Indian cooking, where it is the main ingredient in the famous dish known as sambar.

The spicy, satisfying sambar is made with tamarind (a sweet and sour fruit), and it is always served with dosa or idli, which are made from a fermented rice and lentil batter.

Toor dal has a naturally sweet taste, and it makes for a non-glutinous consistency. The consistency makes it perfect for a wide variety of dal dishes.

Recipes Using Toor Dal

The Black Gram Family

Black gram has been cultivated in India since ancient times, and remains among one of the country’s highest prized protein sources.

Black gram has a mucilaginous texture that is quite unique. It is most well known as the main ingredients in dal makhani (recipe coming soon), which cooks for a long time over slow heat and gets silky smooth.

For this reason, I enjoy urad dal combined with a second variety of dal, so that I get the best of urad dal’s texture without it being overpowering.

Personally, I am fascinated by the split black gram without the skin. Tiny and white in color, it is often used in South Indian cooking as a spice.

To use it as a spice, you cook the split black gram in oil until it caramelizes and softens slightly. It adds a pleasant nutty taste and a firm bite to the dish, which contrasts nicely with other softer foods.

Black gram may also be soaked, ground, and fermented along with rice or broken rice (known as rava) to make batter for dosa and idli, another South Indian basic food.

Black Gram (with skin)

Also known as urad dal or sabat urad

This is the whole bean with a black skin. It is the same size as green gram (mung bean) and moth gram.

Black gram is the main ingredient in dal makhani (butter bean), a popular dish served in the northern Punjab region of India.

Whole Urad Dal (without skin)

This variety is used for making dosa and idli, but I don't stock it since I generally use the split urad dal for this purpose.

Split Urad Dal (without skin)

This is the tiny white pulse that is used as a seasoning in South Indian cooking. I highly recommend buying split urad dal for this use. I will be including it in many recipes. See "How to Prepare Any Vegetable, South Indian Style," for instructions.

Recipes Using Split Urad Dal (without skin)

Spilt Urad Dal (with skin)

Also known as chilke urad dal

I have not used this, and it is not commonly used.

The Green Gram Family

The family of green grams is well worth knowing.

Green gram is an ancient food, reportedly eaten since Vedic times (c. 1500–c. 500 BCE).

Known as the “king of dal” in the East, and mung beans in the West, green gram is an essential ingredient in khichdi.

Khichdi is central to the Ayurvedic healing and cleansing diet.

When mixed with rice in the same pot with ghee and spices, the dish is considered highly nourishing and digestible.

On an Ayurvedic cleanse, a person would consume only kichadi and water.

One does not need to be on a cleanse to appreciate and benefit from the versatile green gram.

In fact whole mung dal was my first Indian recipe that I ever made, and I fell in love with.

You can buy green gram as a whole bean with the skin, split with the skin, or split without the skin.

Whole Green Gram (Mung Beans)

Also known as mung gram, mung bean, sabat moong, or masha

This is the tiny whole bean with a moss green skin that is commonly sold in Western grocery stores.

The small size of this bean makes it quick to cook and highly digestible.

In Indian cooking, this bean is often sprouted and then used to make different dishes. See below for my recipes. The first a sautéed curry, and the second a raw salad with sprouted mung bean and green mango.

BUY WHOLE MUNG BEANS/GREEN GRAM

Recipes Made With Whole Mung Beans

Split Moong/Mung Dal (with skin)

Also known as chilke, or split green gram

These are used mainly for savories and chutneys, but split mung dal can also be used for soups and dals.

Split Moong (without skin)

Also known as moong dal

When used in soups and stews, split moong dal can get a little sticky, so it requires extra water to thin it out.

Split moong dal can also be soaked, drained, and deep fried, and made into a savory snack.

Recipes Made With Split Moong (without skin)

The Brown Gram Family

Moth Gram

Also known as muth, or dew bean

A greenish-brown color distinguishes this bean from green gram or black gram. It is used in soups and stews, and also deep-fried as a crunchy snack.

The Chana Dal Family

Chana dal and chana masala are famous Indian dishes that everyone in the west knows made from chana.

Chana masala is one of my favorite recipes on the Buttered Veg blog.

This recipe is made with what we know as chickpeas or garbanzo beans. In India, chickpeas are known as kabuli chana, or simply chana.

In India there are two different styles of chana, and then one very popular split chana. Chickpea flour, known as "besan" or gram flour in India, is also there.

I have already mentioned the first whole chana. It is essentially the chickpea.

The second is known as desi chana, or kala chana. Kala is the Hindi word for black, and kala chana is black, or black-brown in color.

The split chana is yellow-orange, and it is made from the kala chana with the skin removed. Split chana is used to make the famous chana dal dish.

Kabuli Chana

Also known as chana, chickpeas, or garbanzo beans

Kabuli chana is normally used in its whole form to make flavorful, tomato-based stews.

Another common use is to grind the dried chickpeas into flour, known as gram flour or besan. It is then used as a batter in deep fried savories, steamed savories, or sweets.

Recipes Made With Chickpeas (Kabuli Chana)

Kala Chana

Also known as desi chana or bengal gram

Kala chana is smaller than the chickpea commonly used in the West, and it is black-brown in color.

Kala chana is an ancient variety of chickpea with nearly twice the iron content of other pulses.

It takes much longer to cook than its larger cousin, and it is usually eaten in its whole bean form.

I have used it as a filling for pani puri, which is a wonderfully refreshing Indian snack.

Besan

Also known as gram flour or chickpea flour

This is gluten-free flour made from powdered kala chana.

Besan is very common in Indian cooking. It is used to thicken sauces, to make sweets, and to make a batter for fried treats such as the popular snack food pakoras.

Chana Dal

Also known as bengal split gram

Chana dal is a smaller variety of chickpea, and it is always sold skinned and split. It is extremely popular throughout India.

Due to its consistency and the way it breaks down when cooked, chana dal is used to make thick dals.

It is also commonly used as a seasoning in curries or in Indian pickles.

It is also used to add crunch to snacks. In this case the chana dal is soaked and then deep-fried. Mixed with spices, it makes for a tasty, crunchy dal snack.

It could also be soaked and ground into a wet paste, and then deep fried with spices as a different kind of savory snack.

Dalia

This is roasted chana dal.

The roasting gives the chana dal a rich and nutty taste.

Chana dal is commonly used by South Indians to make coconut chutney.

It can also be ground with other spices and mixed into a spice powder.

2: PULSES USED IN INDIAN COOKING

The Western Pulse Family

The following pulses are used in Indian cooking, and also available in most Western supermarkets.

Chickpeas

Known as chana, or kabuli chana, or garbanzo beans

Chickpeas are normally used in their whole form to make flavorful, tomato-based stews.

Another common use is to grind the dried chickpeas into flour, called gram flour or besan. It is then used as a batter in deep fried savories, steamed savories, or sweets.

Kidney Beans

Also known as rajma, or rajma dal

The most famous use for kidney beans is for the North Indian dish simply called rajma (recipe coming soon).

To make rajma, the whole bean is cooked with tomatoes and spices into a thick, satisfying stew, typically served with rice and roti.

Brown or Green Lentils

Also known as whole masoor

Brown or green lentils are the common lentil available in the West, and they are also used sparingly in Indian cuisine.

Red Lentils

Also known as masoor dal

This is a split red lentil typically used in North Indian cooking. It comes from the brown lentil after the skin is removed.

Red lentils are a relative of the toor dal.

When cooked, masoor dal fully breaks down into a soft consistency, with a light brown color.

This lentil is very soft and does not need to be soaked before cooking.

Cow Peas

Known as lobya, lobia, or black-eyed peas.

Off-white in color, black-eyed peas are distinguished by their black oval markings.

When split and husked they are known as chowla dal. There are quite a few Indian dishes that call for cow peas, particularly in North India.

Recipes Made With Black-Eyed Peas

Peas (whole or split)

Also known as matar dal or vatana

Dried peas are available in yellow or green.

The yellow split pea can be used as a substitute for chana dal or toor dal to make an Indian dal.

Mung Beans

Whole green gram is sold in most American supermarkets as mung beans.

3: SPECIALITY LENTILS

Specialty lentils are available from a number of good suppliers. I highly recommend Timeless Natural Food, which sells all the options listed in this section.

Timeless is a collective of dozens of organic family farms throughout Montana and the surrounding region. Their growing area is located at the foot of the Rocky Mountains.

French Lentils

French lentils are a gorgeous mottled dark blue-green color.

These are heirloom lentils that stay whole after cooking, with spicy flavor notes. Perfect for grain salads and bowls.

Not surprising given their heritage, this is the gourmet lentil of choice for European and American chefs.

Suggested use: Combine these with Indian spices to make soups, salads, and side dishes.

Black Beluga Lentils

Black Beluga lentils are a brilliant pitch black in color, named after their resemblance to caviar.

These are heirloom lentils with a rich flavor that stay whole after cooking, making them the perfect choice in a side dish, grain salad, or grain bowl.

Black lentils are 24 percent protein, which is the highest protein content of any lentil.

Suggested use: Combine these with Indian spices to make soups, salads, and side dishes.

Spanish Pardina Lentils

These are smaller than a typical brown or green lentil, with a thin greenish-brown or greying skin on them.

They have a nutty taste and hold their shape when cooked.

Suggested use: Combine with Indian spices to make soups, salads, and side dishes.

Petite Crimson Lentils

The Petite crimson lentil originated in Turkey and is foundational to its cuisine, with origins tracing back to the Old Testament.

It is among the fastest cooking lentil there is, cooking in 5 to 10 minutes, making it the perfect choice to add to rice, pasta sauce, quick soups, or braised vegetable sides.

Suggested use: Substitute petite crimson for masoor dal in Indian recipes.

Harvest Gold Lentils

These cook up quickly and have a mild and slightly nutty taste.

Great for delicate soups and dips, or add them to a stir-fry or vegetable braise.

Or simply cook them up and season with olive oil, lemon, and spices.

Suggested use: Substitute harvest gold for toor dal or chana dal in Indian recipes.

Where To Buy Indian Dal

Is Dal From India Safe To Eat?

Hmmm … some people may be wondering if it’s safe to eat pulses grown in India, and if this is a good practice from a sustainability perspective?

Since India is still a developing country, I certainly asked these questions. I also looked for locally-grown sources.

Unfortunately, for most of the popular Indian pulses, there are no local sources, and each dal is unique, so it cannot easily be substituted.

There’s nothing to worry about though, because the quality of the pulses grown in India is very good.

Dal isn't like fresh produce either. It is harvested from pods that protect the dal from anything that may be sprayed on them. Think of English peas in a pea pod. That is dal.

I have never had an issue with Indian food quality.

In fact, Indian products that are exported to the U.S. are of the highest quality. They are “export quality.”

Also, the overwhelming majority of farming throughout India is done without the use of chemicals.

There are also a number of certified organic brands from India to choose from, including my recommendations here.

I hope that we will start to grow more pulses here in the United States.

I am confident that if Americans want to eat them, farmers will grow them. It is already starting.

Which Pulses Are Grown In North America?

In North America today we mainly grow black beans, pinto beans, kidney beans, Great Northern beans, chickpeas, and yellow peas.

Lentil and bean growing regions in the U.S. include the Palouse region of eastern Washington, the Idaho panhandle, Montana, and North Dakota.

Canada grows some dal for export to India as well. In fact, Canada is the top lentil producer in the world—accounting for 51 percent of the world’s total, according to Wikipedia.

I recently discovered a fantastic group of farmers in Montana that are growing very high quality organic lentils and marketing them under the brand Timeless Foods.

Timeless sells very high quality specialty and European style lentils, such as French green lentils, black beluga lentils, green lentils, gold lentils, red lentils, Spanish brown lentils, petite crimson lentils, and pardina lentils.

These lentils are typically used to make soups, salads, and side dishes, as compared to Indian dal, which are most often made into flavorful stews, but also desserts, snacks, and powders.

Recommended Brands & Sources

Recommended Brands For Indian Dal

Thanks to online shopping, getting these pulses is still super convenient. You can see some of my Amazon recommendations below.

Swad is the brands I buy the most from the Indian store. It is not organic, but it's based in New Jersey and is still very high quality.

Recommended Brands For Organic Pulses

Organic dal is also wonderful, but it can be nearly twice the cost. It is up to you to choose how much you value the organic label.

The two companies I recommend in this category are pioneers in the organic and natural food industry Shiloh Farms, and Bob's Red Mill. Both suppliers carry a huge range of pulses, grains, and more.

Did you enjoy this post? Let me know your thoughts in the comments below.

For more Buttered Veg lifestyle content, follow me on Pinterest, Facebook, Instagram, and Twitter.

Emeth Dandona

Great Post. But dal is often confused to be only used with PURE VEG. Well, I'm sure the meat lovers would just go nuts for "Dalcha" or Dal Chicken and "Dal Ghost" Which is Dal with goat meat (but can also be cooked with beef) Trust me, check one of these recipes out on Youtube and you will not regret it! 🙂

Andrea

Thanks Emeth for this comment. Good point for meat eaters. I am SURE that meat-based dal would be amazing too 🙂

Chakri

I commend your understanding of most if not all of the dals of India. Truly, it takes more than a lifetime to understand all of these and more, since there are various regional variations for different types and the dishes made out of and included of them.

Andrea

Thank you so much for your feedback. I enjoy Indian cooking, and many things I learned from my mother-in-law. India was where my real introduction to Indian cooking took place. Wish you all the best!

Ritesh Sharma

Great post, you have covered the detailed information of dal.

Thanks for sharing

Andrea

Thank you too! I appreciate your feedback 🙂